Author:

Dharamvir Bharati (25 December 1926 – 4 September 1997) was a celebrated Hindi poet, author, playwright, and social thinker. He served as the chief editor of the widely read Hindi weekly Dharmayug from 1960 to 1987.

In 1972, the Government of India honored him with the Padma Shri for his contributions to literature. His novel Gunahon Ka Devta is regarded as a timeless classic. Another notable work, Suraj Ka Satvan Ghoda, is acclaimed for its experimental narrative style and was adapted into an award-winning film by Shyam Benegal in 1992. His iconic play Andha Yug, set in the aftermath of the Mahabharata war, continues to be staged frequently by theatre groups.

In recognition of his excellence in playwriting, Bharati received the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award in 1988 from India’s National Academy of Music, Dance, and Drama.

Prominent Works of Dharamvir Bharati:

Novels

-

Gunahon Ka Devta (गुनाहों का देवता, 1949): A landmark romantic novel that has earned the status of a classic in Hindi literature.

-

Suraj Ka Satwan Ghoda (सूरज का सातवां घोड़ा, 1952) – The Seventh Steed of the Sun: This short novel, composed of interlinked narratives told by the protagonist Manik Mulla, is considered one of the earliest examples of metafiction in modern Hindi literature. Its title refers to Hindu mythology, where the Sun God’s chariot is drawn by seven horses, symbolizing the days of the week. The book was translated into Bengali by poet Malay Roy Choudhury, who was awarded the Sahitya Akademi Award for it. Shyam Benegal adapted it into a critically acclaimed film in 1992, which won the National Film Award for Best Actor.

-

Gyarah Sapno Ka Desh (ग्यारह सपनों का देश): A novel filled with imaginative and symbolic visions of society.

-

Prarambh va Samapan (प्रारंभ व समापन): A thoughtful exploration of beginnings and endings in life and relationships.

-

Kanupriya: A lyrical retelling of Radha-Krishna's story from Radha’s perspective.

-

Thanda Loha (ठंडा लोहा – Cold Iron)

-

Saat Geet Varsh (सात गीत वर्ष)

-

Sapna Abhi Bhi (सपना अभी भी – The Dream Still Lives)

-

Toota Pahiya (टूटा पहिया – The Broken Wheel): A poetic narrative about how a broken wheel proved to be a turning point for Abhimanyu during the Mahabharata war.

Dramatic Work (Poetic Play):

-

Andha Yug (अंधा युग – The Age of Blindness): A powerful poetic play based on the last day of the Mahabharata war. It serves as an intense allegory for moral decay and the consequences of war. The play has been staged by many renowned Indian theatre directors, including Ebrahim Alkazi, Raj Bisaria, M.K. Raina, Ratan Thiyam, Arvind Gaur, Ram Gopal Bajaj, Mohan Maharishi, Bhanu Bharti, and Pravin Kumar Gunjan.

Story Collections:

-

Dron Ka Gaon (द्रों का गाँव)

-

Swarg aur Prithvi (स्वर्ग और पृथ्वी – Heaven and Earth)

-

Chand aur Tute Hue Log (चाँद और टूटे हुए लोग – The Moon and the Broken People)

-

Band Gali Ka Aakhri Makaan (बंद गली का आखिरी मकान – The Last House in the Dead-End Street)

-

Saas Ki Kalam Se (सास की क़लम से – From a Mother-in-law’s Pen)

-

Samasta Kahaniyan Ek Saath (समस्त कहानियाँ एक साथ – Collected Stories Together)

Essays:

-

Thele Par Himalaya (ठेले पर हिमालय – The Himalayas on a Cart)

-

Pashyanti Kahaniyan: Ankahi (पश्यंती कहानियाँ: अनकही – Unspoken Stories)

-

Nadi Pyasi Thi (नदी प्यासी थी – The River Was Thirsty)

-

Neel Jheel (नील झील – The Blue Lake)

-

Manav Moolya aur Sahitya (मानव मूल्य और साहित्य – Human Values and Literature)

-

Thanda Loha (ठंडा लोहा – Cold Iron)

These works reflect Bharati’s rich literary legacy and his deep engagement with culture, human values, mythology, and social thought.

Awards and Honors of Dharamvir Bharati:

-

Padma Shri – Awarded by the Government of India in 1972 for his outstanding contribution to literature.

-

Rajendra Prasad Shikhar Samman – A prestigious literary honor.

-

Bharat Bharati Samman – One of the highest literary awards conferred by the Uttar Pradesh government.

-

Maharashtra Gaurav Award – Conferred in 1994, recognizing his literary achievements.

-

Kaudiya Nyas Samman – Honored for his work in cultural and literary fields.

-

Vyasa Samman – Acknowledging his excellence in Hindi literature.

-

Valley Turmeric Best Journalism Award (1984) – For his exceptional contributions to the field of journalism.

-

Maharana Mewar Foundation Award (1988) – Recognized as the Best Playwright of the year.

-

Sangeet Natak Akademi Award (1989) – Conferred by the Sangeet Natak Akademi, Delhi, for his distinguished work in Hindi playwriting.

.jpeg)

The book I received, features a cover with two terracotta-colored stone sculptures of human figures seated on stone steps, facing away from the viewer. These figures represent the central characters, Chandar and Sudha.

On the left side sits the figure symbolizing Sudha. Her posture and hand placement suggest an emotion of ibadat—a quiet, reverent act of worship—directed toward the figure on the right, representing Chandar. Chandar, meanwhile, is shown gazing up at the sky, capturing a sense of helplessness and emotional conflict, which reflects the central tension of the novel.

The terracotta sculptures and the stepped stone architecture appear inspired by ancient North Indian structures—perhaps reminiscent of Varanasi, Allahabad, or traditional educational institutions—beautifully echoing the cultural and historical backdrop of the story.

My Views on This Book:

The plot of Gunahon Ka Devta is fairly simple and, in some ways, predictable. At its heart, it is the story of a silent, unspoken love between Chandar and Sudha—a love both hold sacred, yet never express openly, nor feel the need to validate. They deeply wish for each other’s happiness, but remain entangled in societal ideals and emotional morality, choosing to sacrifice their love in the name of righteousness.

From the very beginning, the novel offers glimpses of affection, tension, and emotional conflict between them. Sudha treats Chandar with the reverence of a devotee, seeing him almost as a deity. Chandar, often unknowingly, cares for her with a gentle, protective affection.

Dr. Shukla—Sudha’s father—not only serves as Chandar’s mentor and guide but also treats him like a member of the family. This complex web of emotional, intellectual, and familial bonds shapes the very foundation of the narrative.

Sudha is the emotional center of the entire novel. We experience her primarily through Chandar’s perspective. She is portrayed as a simple yet intelligent girl, full of innocent charm and playful mischief. Shy and demure at times, yet vibrant and free—like a butterfly fluttering through the lives of Dr. Shukla and Chandar.

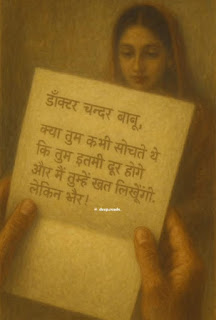

The description—

"घर भर में अल्हड़ पुरवाई की तरह तोड़-फोड़ मचाने वाली सुधा, चंदर की आंख के एक इशारे से शांत हो जाती थी।"

—beautifully captures their bond. Another striking line:

"चंदर का चेहरा देखकर छिपजाने वाली सुधा इतनी ढीठ हो गई थी कि उसका सारा विद्रोह, सारी झुँझलाहट, मिजाज की सारी तेजी, सारा तीखापन और सारे लड़ाई-झगड़े, सबकी दिशा बदलकर अब चंदर की ओर केन्द्रित हो गए थे..."

—reflects the emotional transformation Sudha undergoes in Chandar’s presence.

She becomes calm, soft-spoken, and composed in front of others, yet in front of Chandar, she returns to her mischievous, playful self—restless until she has teased, annoyed, or argued with him. The sense of belonging they share is so pure and effortless, it feels as natural as the crispness of autumn or the glow of dawn.

Sudha is portrayed as a deeply caring girl, with a naturally nurturing—almost motherly—nature. As the author writes:

"मोटर या बिजली खराब हो जाने पर वह थोड़ी-बहुत इंजीनियरिंग भी कर लेती थी और उसमें मातृत्व का अंश इतना था कि हर नौकर और नौकरानी उससे अपना सुख-दुख कह लेते थे। पढ़ाई के साथ-साथ घर का सारा काम-काज करते हुए उसका स्वास्थ्य भी कुछ बिगड़ गया था और वह अपनी उम्र के हिसाब से कुछ अधिक शांत, संयमित, गंभीर और बुज़ुर्ग जैसी लगने लगी थी। मगर अपने पापा और चंदर — इन दोनों के सामने उसका बचपन फिर से इठलाने लगता था।"

This passage beautifully captures the essence of Sudha’s character—responsible beyond her years, yet childlike and playful when around her two closest people: her father and Chandar. Her emotional maturity blends seamlessly with her innocence, making her both graceful and endearing.

.jpeg)

Chandar and Sudha are like one soul in two bodies. Chandar is not just a guest in the Shukla household—he is one of them. Having run away from his own home and even fought with his mother in pursuit of education, he was embraced wholeheartedly by Dr. Shukla, his former teacher, who gave him not just shelter but also a fatherly place in his life.

In the first half of the novel, Chandar appears to be a man of high moral values. He is ambitious, emotionally perceptive, and deeply observant. His idealism and philosophical commitment to humanity are evident in the following excerpt:

"उसने निश्चय किया था कि वह अपने देश और अपने युग के आर्थिक पहलुओं का गहराई से, अपने ढंग से विश्लेषण करेगा। उसे आशा थी कि एक दिन वह ऐसा समाधान खोज निकालेगा जिससे मानव की बहुत-सी समस्याएँ हल हो जाएँगी। यदि आर्थिक और राजनीतिक क्षेत्र में इंसान खूंखार जानवर बन गया है, तो एक दिन दुनिया उसकी एक पुकार पर देवता बन सकेगी।

इसीलिए जब वह कानपुर की मिलों के मजदूरों के वेतन का चार्ट बनाता था, या उपयुक्त साधनों के अभाव में मर जाने वाली गरीब औरतों और बच्चों का लेखा-जोखा करता था — तो उसके सामने न तो अपना करियर होता था, न प्रतिष्ठा, और न ही डिग्री का सपना।"

This gives us a powerful insight into Chandar’s character. His motivations are not driven by fame or personal gain but by a genuine desire to understand and resolve the deeper issues of society. He is a thinker, a dreamer, and a man torn between his ideals and the emotional conflicts of life.

Together, Chandar and Sudha form the emotional core of Gunahon Ka Devta. Their relationship is intimate yet restrained, sacred yet unfulfilled—symbolizing the conflict between love, duty, and societal expectations.

Chandar appears to be ironically emotional. While he often wounds Sudha on a deeply emotional level—sometimes with cold logic, other times through calculated silence—he remains remarkably humble and sensitive toward everyone else in society. This irony is especially noticeable when we see his compassion for societal suffering contrasted with his emotional rigidity in personal relationships.

For instance, the author writes:

"चंदर थोड़ा भावुक था। एक बार जब उसने अपने शोध कार्य के सिलसिले में यह पढ़ा कि अंग्रेज़ों ने अपनी पूँजी लगाने और व्यापार फैलाने के लिए किस तरह मुर्शिदाबाद से लेकर रोहतक तक भारत के ग़रीब से ग़रीब और अमीर से अमीर बाशिंदों को अमानवीयता से लूटा, तो वह फूट-फूट कर रो पड़ा था।"

This passage shows his deep empathy for historical injustices and the suffering of others. However, despite such sensitivity, he never actively participated in politics. The reason was clear to him—most of his friends who joined politics eventually gained fame and prestige but lost their ideals and emotional depth.

What makes Chandar’s character even more complex is the way he is perceived by Sudha. To her, Chandar is not just a person—he is a deity. She often refers to him as a "Devta" (god-like being), which symbolizes her reverence, her love, and also her helplessness in front of his idealism. This god-like image that Sudha carries for Chandar becomes the very distance that keeps them apart, even when their souls ache for union.

We can see the misogyny of Chandar, as Sudha once says:

"मिस पम्मी, शायद इसी वजह से आप उसे इतनी पसंद आईं — क्योंकि आप ज़्यादा बाहर नहीं जातीं; उसे लड़कियों का बार-बार बाहर आना-जाना और ज़्यादा आज़ादी पसंद नहीं है।"

From the very beginning, Chandar appears to be the "Devta" of patriarchy. He has strong beliefs and principles about life and has built an image of a trustworthy person in front of Dr. Shukla and even the household helpers. Everyone is impressed by the purity and transparency of his character and values. Binati has immense faith in him from the very start. Even Pammi is captivated by Chandar’s ideals and morality. Despite her flirtatious behavior, Chandar successfully maintains both emotional and physical distance from her.

The story can be divided into two parts: before and after Sudha’s marriage. Chandar is chosen to convince Sudha to get married. As a rebellious girl, Sudha refuses, but Chandar takes it upon himself to persuade her. He appears manipulative from the beginning. He doesn’t allow Sudha to go with her friends on a picnic, and Sudha, being so obedient, waits for him to return home just to seek his permission to attend a friend's Qawwali program. When he doesn’t return, she keeps crying and eventually falls asleep while waiting. Her dependence on Chandar is beyond imagination and limits.

Even regarding her marriage, after Dr. Shukla, Chandar feels it is his responsibility to find a suitable groom for Sudha. When he finds out that her prospective husband is none other than Kailash Mishra—someone he once joined in a political movement—he immediately agrees to the match.

Sudha’s obedience to him is clearly seen in this life-altering conversation:

आँखों में, वाणी में, अंग-अंग से सुधा का आत्मसमर्पण छलक रहा था।

After that, Chandar tries to manipulate Sudha emotionally. But when she doesn’t agree, he reacts violently—physically abusing her. He slaps her brutally, as described in the line:

Even in that painful moment, we observe the depth of Sudha’s pure and selfless love for Chandar. Despite being hurt, she is more concerned about him than herself. She kneels beside him, puts her head on his knees, and asks with a heavy voice:

Neither Chandar nor Sudha openly confesses their love. In fact, Sudha herself questions the very idea of whether she ever loved anyone at all, in this emotional and reflective conversation:

"नहीं, हमें तो कभी नहीं बताया," चंदर बोला।

"तब तो हमने प्या-वार नहीं किया। गेसू यूँ ही गप्प उड़ा रही थी..."

One can see Sudha’s love as something more maternal than romantic. Like a mother, she never expects anything in return. Her care is silent, deep, and unconditional. In fact, the way she behaves at times suggests she never even saw Chandar as a lover. In this brief, quiet moment, that becomes evident:

"चंदर एक फीकी हँसी हँसकर रह गया और चुपचाप सुधा की ओर देखने लगा। सुधा चंदर की निगाह से सहम गई।"

"चंदर की निगाह में जाने क्या था — एक अजीब-सा पथराया सूनापन, किसी अनजाने दर्द की अमंगल छाया, किसी पीड़ा की मूक आवाज़, किसी पिघलती हुई सी उदासी... और वह भी गहरी, जाने कितनी गहरी... और चंदर था कि एकटक देखे जा रहा था, अपलक।"

"सुधा को जाने कैसा लगा। यह अपना चंदर तो नहीं, यह उसकी निगाह तो नहीं है। चंदर ने कभी इस तरह नहीं देखा था। चंदर की निगाह में तो शरारत होती थी, डाँट होती थी, दुलार होता था, करुणा होती थी।"

"पर इस निगाह में कुछ और ही था — कुछ ऐसा जिससे सुधा बिल्कुल अपरिचित थी, जो आज चंदर में पहली बार दिखाई पड़ रहा था। सुधा को जैसे डर लगने लगा, जैसे वह काँप उठी। नहीं, यह कोई दूसरा चंदर है जो उसे इस तरह देख रहा है। यह कोई अजनबी है, किसी दूसरे देश का व्यक्ति — जो सुधा..."

As a reader, we can clearly see that this moment marks an internal shift in Chander. He begins to recognize his suppressed feelings for Sudha—feelings that until now he either ignored or buried under the weight of morality and social expectations.

Chander becomes emotionally disturbed the very first time Sudha’s Buaji mentions her marriage. His discomfort and inner turmoil are reflected in this intense description:

This visceral reaction reveals that even though Chander had always maintained a distance in the name of principles, the idea of Sudha belonging to someone else shakes his core.

He later tries to articulate and understand Sudha’s emotions, while simultaneously expressing his own unspoken pain:

This passage not only expresses the tragedy of their bond, but also underlines the conflict between love and idealism, between emotion and social responsibility. Chander’s awakening is painful and too late—by the time he realizes the depth of his love, circumstances have already taken a turn from which there is no return.

But Chander manipulates her emotionally and convinces her to agree to the marriage by saying:

Sudha agrees, but her heart is breaking.

Throughout the novel, Chander is often referred to as a devta (god). Almost all the female characters—Sudha, Binati, Pammi, and even Ghesu—view him in this divine light. Binati expresses her reverence for Chander by saying:

To me, Sudha feels like a modern-day Meera—completely devoted to her Krishna (Chander), even after she gets married to someone else, just like Meera was married to Bhoj Raj. Her faith is absolute, unquestioning. It is the woman who shows immense trust in God and religion, and yet, it is often the same God and religion that abandon and curse her.

This contradiction is seen in mythology too—Lord Ram exiled his pregnant wife Sita to protect his throne and honor. Yet, women continue to worship him with love and devotion. In this novel, Chander represents that same idea of devta—a godlike man who always protects his own image and distances himself from emotional accountability.

Sudha, on the other hand, accepts all the stains, all the blame, without hesitation. This is clearly seen in the Nankhatai scene:

"चंदर सुधा की इस बात पर हँस पड़ा और उसने पानी में हाथ डुबोकर बिना पूछे सुधा के आँचल में हाथ पोंछ दिए — स्याही के। फिर बेतकल्लुफ़ी से नानखटाई उठाकर खाने लगा।"

And again, in another scene when Sudha is upset about her marriage and cleaning the engine of a car:

और सचमुच आँचल में हाथ पोंछकर बोली — 'चलो, अंदर चलो, उठ बनती! बलैया कहाँ की!"

These details reveal Sudha’s unconditional, pure love and the shallowness of Chander’s supposed love. He uses Sudha repeatedly to maintain his image of a principled and trustworthy man.

Sudha is in platonic love with Chander, and Chander too "believes" that he shares the same kind of love for her. But when Sudha falls ill before the marriage, her health continues to decline as the wedding day draws closer. Even then, Chander chooses to distance himself. He avoids contact with Sudha during her most vulnerable moments.

Many readers find this novel sentimental for different reasons. But for me, the most emotional and heartbreaking part is Sudha’s marriage. She was a bright, cheerful girl who wanted to study, who deeply loved her father and Chander—yet both of them betrayed her.

"ब्याह-शादी को कम से कम भावनाओं की दृष्टि से नहीं देखता। यह एक सामाजिक तथ्य है और उसे उसी दृष्टिकोण से देखना चाहिए। शादी में सबसे बड़ी बात होती है — सांस्कृतिक समानता।

और जब अलग-अलग जातियों में अलग-अलग रीत-रिवाज़ होते हैं, तो एक जाति की लड़की दूसरी जाति में जाकर कभी भी अपने को ठीक से संतुलित नहीं कर सकती।

और फिर, एक बनिये की व्यापारिक प्रवृत्तियों की लड़की और एक ब्राह्मण की अध्ययन-प्रधान वृत्ति का लड़का — इनकी संतान न इधर विकसित हो सकती है न उधर। यह तो सामाजिक व्यवस्था को व्यर्थ के लिए असंतुलित करना है।"

Dr. Shukla holds rigid, conservative views about caste. He is completely against inter-caste marriages and sees them as a threat to societal balance. When Chander indirectly tries to explore his views on inter-caste marriage, he carefully poses a question:

"हाँ, लेकिन विवाह को आप केवल समाज के दृष्टिकोण से क्यों देखते हैं? व्यक्ति के दृष्टिकोण से भी देखिए। अगर दो विभिन्न जातियों के लड़का-लड़की आपस में मानसिक संतुलन बेहतर बना सकते हैं, तो क्यों न विवाह की इजाज़त दी जाए?"

To this, Dr. Shukla responds with firm disapproval. He believes love marriages are mostly unsuccessful and should not be used to challenge societal norms:

"ओह, एक व्यक्ति के सुझाव के लिए हम समाज को क्या नुकसान पहुँचा दें! और यह कैसे निश्चित किया जा सकता है कि विवाह के समय यदि दोनों में मानसिक संतुलन है, तो विवाह के बाद भी वह बना रहेगा ही?

मानसिक संतुलन और प्रेम जितना अपने मन पर आधारित होता है, उतना ही बाहरी परिस्थितियों पर भी। क्या पता विवाह के समय की परिस्थिति दोनों के मन पर कितना प्रभाव डाल रही हो और वह संतुलन बाद में रह पाएगा या नहीं?

और मैंने तो लव-मैरिजेज (प्रेम-विवाह) को प्रायः असफल होते देखा है। बोलो, है या नहीं?" — डॉ. शुक्ला ने कहा।

Chander, with great courage, tries to counter this with a hopeful view of true love:

"हाँ, प्रेम-विवाह अक्सर असफल होते हैं, लेकिन यह भी सम्भव है कि वह प्रेम ही न रहा हो। जहाँ सच्चा प्रेम होगा, वहाँ विवाह कभी असफल नहीं होगा," चंदर ने बहुत साहस करके कहा।

But Dr. Shukla dismisses this as mere romantic idealism:

"ओह! ये सब साहित्य की बातें हैं। समाजशास्त्र और वैज्ञानिक दृष्टिकोण से देखो!" — डॉ. शुक्ला बोले।

This very conversation reveals the depth of Dr. Shukla's strong beliefs against love and inter-caste marriages. Despite being a renowned and respected professor, he rigidly decides the future of his daughter, Sudha. Even after Sudha expresses her desire to pursue higher education and avoid marriage, Dr. Shukla emotionally manipulates her and proceeds with her wedding to Kailash Mishra.

After the marriage ceremony, Sudha turns to Chander and shares that her father has stopped speaking to her. Only then does Chander call Dr. Shukla to meet his daughter. In a deeply emotional moment, Sudha cries and seeks comfort from her father. But instead of showing compassion, Dr. Shukla coldly remarks:

"मुझे यह रोना अच्छा नहीं लगता। यह भावुकता क्यों? तुम पढ़ी-लिखी लड़की हो। इसी दिन के लिए तुम्हें पढ़ाया-लिखाया गया था! भावुकता से क्या फ़ायदा?"

This behavior from the so-called open-minded Dr. Shukla—who once took a firm stand for his niece Binati by stopping her marriage—stands in stark contrast to his silence and passivity regarding his own daughter’s suffering. He never once tries to intervene or help Sudha, even after learning that Kailash, her husband, is forcefully intimate with her, and that her physical and emotional health is deteriorating day by day.

On the other hand, when Dr. Shukla discovers that Binati’s fiancé has physical disabilities, he immediately calls off the marriage, despite societal pressure. He educates Binati and supports her dreams—dreams that once belonged to Sudha.

This parallel exposes the deep hypocrisy in Dr. Shukla’s character: he fights for his sister’s daughter, but fails to protect or even emotionally support his own child.

His hypocrisy is further revealed in subtle everyday actions. For example, though he dines at social events with people of all backgrounds, in his own home, Chander—who belongs to a lower caste—often eats separately. He usually sits on the veranda or outside the kitchen area, restrained both by social customs and his own internalized limitations. Despite being accepted as a member of the family in every other way, Chander is never allowed to cross the invisible boundaries of caste within the household. This double standard—between ideology and practice, between public openness and private conservatism—exposes the contradictions that define Dr. Shukla's character. His intellect and progressive image are repeatedly compromised by his actions, particularly in the treatment of Sudha, making him one of the novel’s most layered and conflicted figures.

Dr. Shukla takes a firm stand for Binati but never utters a word when it comes to his own daughter, which is deeply saddening. Binati is Dr. Shukla’s sister’s daughter. Her father passed away when she was born, and ever since, her mother has emotionally tormented her, constantly blaming her for his death. In a deeply regressive and superstitious mindset, her mother tries to prove that Binati is “unlucky” for the family. This reveals the backward and harmful thinking that women, especially girls, are often subjected to in the name of fate or misfortune.

Binati suffers greatly under this emotional burden. Unlike Sudha, she is not very ambitious. She is a simple girl from a village background, but life eventually gives her some opportunities. Binati is obedient and seems to be emotionally mature as well.

She, too, sees Chander as a 'devta'—a godlike figure. This is clearly seen in the following conversation:

बिनती थोड़ी देर तक चंदर की ओर एकटक देखती रही। चंदर ने उसकी निगाहें चुराईं और बोला, "क्या देख रही हो, बिनती?"

"देख रही हूँ कि आपकी पलकें झपकती हैं या नहीं," बिनती बहुत गंभीरता से बोली।

"क्या?"

"इसलिए कि मैंने सुना है — देवताओं की पलकें कभी नहीं गिरतीं।"

चंदर एक फीकी हँसी हँसकर रह गया।

"नहीं, आप मज़ाक न समझिए। मैंने अपनी ज़िंदगी में जितने लोग देखे, उनमें आप जैसा कोई भी नहीं मिला। कितने ऊँचे हैं आप, कितना विशाल हृदय है आपका!"

This tender moment reflects how idealized Chander becomes in the eyes of every woman in the novel. Binati, too, projects godlike purity and moral superiority onto him. Her words reveal a quiet reverence that mirrors how deeply Chander’s image has been mythologized by those around him—even by someone like Binati, who comes from pain, not privilege. After Sudha, it is Binati who trusts Chander blindly. Binati’s marriage was originally planned to take place before Sudha’s, but due to social pressures, Sudha had to be married first. In Binati’s case, her would-be in-laws demanded dowry, and Dr. Shukla fulfilled those demands. However, during the wedding ceremony, it was discovered that the groom had no fingers and was also not well-educated. The marriage was immediately called off.

After Sudha, Binati is perhaps the most pitiable character in the novel. She suffers immensely, but her pain often gets overshadowed by the emotional turmoil of other characters. Following Sudha’s departure, it is Binati who takes care of Chander. She repeatedly tries to restore his moral compass when he starts to drift away, especially during his involvement with Pammi.

Pammi is one of the most tragic and unfortunate female characters in the story. A divorced Anglo-Indian woman, Pammi enters Chander’s life at a time when he is emotionally broken after Sudha’s marriage. Pammi’s brother, Berty, also carries a deep emotional scar. He was madly in love with his wife, who had betrayed him. However, in a tragic twist, she later returned to care for him during his illness, and died while giving birth to their child. In her memory, Berty planted an entire garden of roses.

Interestingly, Berty’s character development is far more nuanced and compelling than Chander’s. Chander first meets Berty and Pammi before Sudha’s marriage, at a time when Berty was mentally unstable and haunted by hallucinations of his wife in the rose garden. His madness was rooted in a deep, desperate kind of love — a hauntingly beautiful devotion. However, when Berty returns from a long vacation, he is a completely changed man. He brings with him a new girlfriend and a baby parrot as a gift. In a surprising move, he gifts the parrot — his wife's last memory — to his girlfriend for her birthday. When Chander questions him about it, Berty replies with an unsettling philosophy:

"मैं तो समझता हूँ कि कोई भी पति अपनी पत्नी को अगर कोई अच्छा उपहार देना चाहे — तो वह है: एक नया प्रेमी। और कोई भी प्रेमी अगर अपनी रानी को कोई अच्छा उपहार देना चाहे — तो वह है: एक पति।"

This philosophy deeply unsettles Chander, who is already restless after Sudha’s marriage. Ironically, it was Chander himself who had manipulated Sudha into marrying Kailash Mishra. And even when Sudha later confides in Chander about the traumatic physical intimacy in her marriage, Chander dismisses it as a normal part of marital life.

"चन्दर, उनमें सब कुछ है। वे बहुत अच्छे हैं, बहुत खुले विचारों के हैं। मुझे बहुत चाहते हैं, मुझ पर कहीं से कोई बंधन नहीं है। लेकिन इस सारे स्वर्ग का जो मूल्य चुकाना पड़ता है, उससे मेरी आत्मा का कण-कण विद्रोह कर उठता है!"

और सहसा घुटनों में मुँह छुपाकर रो पड़ी।

"कैसे करूँ, चन्द! वह इतने अच्छे हैं और इसके अलावा इतना अच्छा व्यवहार करते हैं कि मैं उनसे क्या कहूँ? कैसे कहूँ?" सुधा बोल उठी।

"जाने दो सुधा, जैसी ज़िंदगी हो, वैसा ही निभाव करना चाहिए — इसी में सुंदरता है। और जहाँ तक मेरा खयाल है, वैवाहिक जीवन के प्रारंभिक चरण में ही यह नशा रहता है। फिर किसे यह सब सूझता है?"

Sudha time and again indicates that she is not happy in her marriage. because the spouse was good enough, mature enough but not human enough to understand sudha and her body. sudha writes in a letter also that--

''मेरे भाग्य!

तुम्हारी अभागी — सुधा।

But instead of helping her, Chandar gets influenced by the shallow philosophy of the pervert Berty!

"अगर दिल से प्यार करना चाहते हो और चाहते हो कि वह लड़की जीवन भर तुम्हारी कृतज्ञ रहे — तो तुम उसकी शादी करवा दो... यही लड़कियों के सेक्स जीवन का अंतिम सत्य है! हा! हा! हा!" बट्टी ज़ोर से हँस पड़ा।

चन्दर को ऐसा लगा जैसे किसी जलती हुई आग की लपट उसे भीतर तक जला रही हो। उसी ने तो यही किया था सुधा के साथ, वही जो अब बट्टी इतने विचित्र, व्यंग्यपूर्ण स्वर में कह रहा था।

उसे लगा जैसे इस लोक में सारा जीवन विकृत दिखाई देने लगा है। जहाँ साधना की पवित्रता भी कीचड़ और पागलपन में उलझकर गंदा हो जाती है। छिः! कहाँ बट्टी की बातें — और कहाँ उसकी सुधा...!

These very thoughts of Berty trigger something in Chandar. After that, instead of understanding Sudha's pain, he becomes angry with her. He begins to believe that sex is the only truth in any love relationship. He convinces himself that Sudha, too, desires physical intimacy but pretends otherwise. He even expresses this to Binati, saying —

"सब समझता हूँ मैं — कैसा दोहरा नाटक खेलती हैं लड़कियाँ! इधर अपराध करना और उधर मुख़बिरी करना!"

"पता नहीं मैंने क्या अपराध किया चन्दर, जो तुम्हारा स्नेह खो बैठी।"

Dharamveer Bharti tried to portray Chandar as the strongest character of the novel, but I think Chandar is actually the weakest. He doesn’t have his own strong perceptions, and even if he does, they are limited to the comfortable, idealistic phases of his life. The moment life presents him with challenges, he gets trapped in overthinking. Instead of confronting reality with clarity, he fills the gaps in his weak thoughts with the perverted philosophies of Berty.

Chandar becomes physically involved with Pammi. Before that, he discusses the topics of love and sex with her. Pammi tells him that the love he feels for Sudha is nothing but a form of hypnotism. She even says that Binati too is hypnotized by Chandar’s so-called love. Pammi considers the feelings between Chandar and Sudha as nothing but a psychological illusion — a simple, ordinary case of emotional hypnotism. Shockingly, Chandar also accepts this logic, which can be seen in this dialogue:

"यह एक और तरह की परिस्थिति है। देखो कपू, क्या तुमने हिप्नोटिज़्म (Hypnotism) के बारे में नहीं पढ़ा?"

चन्दर को लगा जैसे बहुत कुछ सुलझ गया। एक क्षण में ही उसके मन का बहुत-सा भार उतर गया।

Again, to justify his own weaknesses and fill the loopholes in his character and morals, Chandar adopts Pammi's ideas as convenient reasoning. Instead of confronting his inner conflicts, he uses her shallow philosophy to defend his own moral collapse.

On the other hand, Sudha frequently writes in her letters that her in-laws are very kind to her. Even her husband is caring — except for his physical expectations. This care is evident in his actions: the way he looks after her, remembers her medicines, and ensures her comfort. Despite all this affection from her husband and his family, Sudha still longs for the divine, pure love she once shared with Chandar — a love untouched by the complications of physical intimacy.

This yearning is expressed in one of her letters when she writes:

"चन्दर, एक बात कहूँ — अगर बुरा न मानो तो?"

ज्यों-ज्यों दूर बढ़ती जा रही हूँ, त्यों-त्यों तुम्हारी पूजा की प्यास और गहरी होती जा रही है।

काश! मैं सितारों के फूलों और सूरज की आरती से तुम्हारी पूजा कर पाती..."

sSudha ignored all the affection she received from her in-laws and her husband, and continued to love Chandar unconditionally — without expecting anything in return. Her love remained steadfast, spiritual, and selfless. In contrast, Chandar, who was once considered a symbol of platonic devotion, distances himself from Sudha's pure love over something as trivial as the touch of Pammi's lips. His fall from grace is starkly evident in this passage:

"माथे पर पम्मी के होंठों की गुलाबी गर्मी चंदर की नसों को गुदगुदा गई। वह क्षण-भर के लिए खुद को भूल गया... पम्मी के रेशमी फ्रॉक की मुलायम सरसराहट, उसकी देह की अलभ्य गरमाहट और उसके स्पर्श के जादू में वह धीरे-धीरे डूबता चला गया। उसके अंग-अंग में सुबह की शबनम सी ठंडक और कंपन उतरने लगी। पम्मी उसकी बालों को अपनी उंगलियों से सुलझाती रही..."

And on the other hand, after forcing Sudha into marriage with Kailash, when Sudha shares the pain of her sexual life, Chandar completely misinterprets it. By now, he knows very well that he will never have Sudha in his life. So, he turns to Pammi as a form of escapism — escapism from the pain of losing Sudha, escapism from the prejudice that Sudha might be enjoying her married life with another man, and escapism from the emptiness of his sacred inner world where once resided the goddess of love — Sudha. As a reader, I observed that Bhartiji tried to portray Chandar as a "Devta," and even his moral downfall is depicted in a way that resembles a "fallen angel," which is evident in the line:

"सात चाँद की रानी ने आखिर अपनी निगाहों के जादू से सन्नाटे के प्रेत को जीत लिया।"

This poetic expression symbolizes the moment Pammi's allure overcomes the silence and void within Chandar — not as a lover, but as a man who once stood at the pedestal of virtue and now seeks refuge in desire.

It seems that Bharti ji is trying to justify the fall of Chandar — his actions, his moral decline — by romanticising his pain. After Sudha, there were Pammi and Binati. Binati, in particular, got emotionally close to Chandar; she supported him with genuine care and affection. On the other hand, Pammi represented physical intimacy. Yet, Chandar never found himself emotionally drawn to Binati. Instead, he gravitated toward Pammi — not for emotional solace, but for physical escape. This clearly reveals that Chandar, the so-called 'devta,' was more tempted by sensual comfort than emotional depth. And to justify this behaviour, Bharti ji portrays Chandar's downfall not as a moral failure, but as the tragic arc of a 'fallen angel.' He began the novel as a 'devta,' and ended it as Gunahon Ka Devta.

Days passed in the company of Pammi. Meanwhile, Binati left the house to return to her village for her marriage, but due to unforeseen circumstances and societal complications, the wedding was cancelled. When Binati returned, Chandar — who had often taken his frustration out on her — tried to express sympathy. However, Binati, deeply hurt and emotionally distanced, rejected this sympathy. This is evident in the moment when Chandar asks,

This behaviour of chandar shows the very narcissistic personality of him. Chandar is painted as an idealist, a thinker torn between societal norms and emotional truth. But as the story unfolds, he exhibits:

-

Narcissistic tendencies, using the excuse of “sacrifice” to mask his emotional cowardice.

-

Possessiveness without responsibility — he wants Sudha’s love but refuses to claim it.

-

Hypocrisy — he explores physical and emotional intimacy elsewhere but expects Sudha to remain ideal and untouched.

Chandar wants to be revered, not challenged. He’s less a ‘devta’ and more a confused man hiding behind the facade of virtue. from the very begning it can be seen through these points:

1. Self-Centered Idealism Disguised as Morality

Chandar repeatedly chooses his own "higher ideals" over the emotional well-being of others. He justifies hurting Sudha by claiming that their love should remain "pure, untouched by marriage" — but in reality, he uses moral ideals as a shield to avoid emotional vulnerability and decision-making.

❝He constantly asserts what is "right" and "pure", but only when it suits his ego.❞

2. Emotional Manipulation of Sudha

Chandar doesn’t explicitly express his love for Sudha until it's too late — yet he expects her to emotionally revolve around him. He gets jealous, possessive, and emotionally crushed when Sudha is married off — but when she had longed for commitment, he remained distant under the guise of sacrifice.

❝He wanted Sudha to worship him like a "devta", but not claim him like a lover.❞That need for admiration without reciprocity is a classic narcissistic trait.

3. Objectification of Women’s Affection

Chandar’s relationships with Binti and later Pummy show how he seeks emotional or physical comfort from women when it suits his needs, but discards or distances himself from them when deeper connection or responsibility is required.

-

He seeks Binti’s warmth when Sudha is gone.

-

He enters a physical relationship with Pummy, despite emotional confusion.

Yet in all cases, he remains emotionally unavailable, and when the woman asserts her individuality, he withdraws or even insults her.

4. Lack of Accountability

Chandar often intellectualizes his actions rather than confronting the emotional damage he causes.

❝Instead of admitting he failed Sudha, he hides behind "life’s circumstances", "destiny", or "ideals".❞

Even in his regret, he centers his own pain more than the pain of those he has hurt.

5. Devta Complex (God Complex)

The very title Gunahon Ka Devta reflects Chandar's internalized image of himself — someone who is above base human instincts, someone “worshipped” by others (especially women), and someone too divine to make human errors — despite constantly making them.

Sudha, in her letters, continues to call him “mere devta”, showing how even she is trapped in that illusion he cultivated.

But again, Chandar’s wavering mind gets triggered by the incident involving Gaisu. Gaisu is Sudha's best friend. Bharti ji describes their friendship in the most beautiful manner —

बातों में छोटी से छोटी और बड़ी से बड़ी—किस तरह की बातें होती थीं, यह वही समझ सकता है जिसने कभी दो अभिन्न सहेलियों की एकांत वार्ता सुनी हो।

This illustrates the emotional yet intellectually grounded friendship between Sudha and Gaisu. Gaisu was in love with her cousin Akhtar, and she believed her marriage was going to be arranged with him. After completing her exams, she went to Nainital, where she thought her wedding with Akhtar would take place. However, in reality, Akhtar's mother preferred Gaisu's sister, and eventually, Akhtar married her instead. What deeply stings is that Akhtar didn’t even attempt to convince his mother about his feelings for Gaisu — he happily accepted the marriage.

Gaisu, heartbroken, did nothing but accept her fate. She continued to love Akhtar silently, in a one-sided way, even as Akhtar moved on and lived happily in his marriage. When Gaisu came to Dr. Shukla's house, Chandar learned about her tragic love story. Chandar, shocked, claimed that Akhtar had betrayed Gaisu. But to his surprise, Gaisu firmly refused to blame Akhtar. Instead, she calmly stated that there must have been some compulsion due to which Akhtar had to marry her sister.

Chandar, astonished by her unwavering faith and grace, asked whether she had ever confronted Akhtar about this. In response, Gaisu replied —

Chandar suggests to Gaisu that she should take revenge on Akhtar by marrying someone else. But Gaisu, deeply disturbed by this shallow suggestion, firmly rejects the idea. She says —

''बदला!'' गेसू मुस्कराकर बोली, ''छिः, चन्दर भैया! बदला, गुरेज़, नफ़रत — इससे आदमी न कभी सुधरा है, न सुधरेगा। बदला और नफ़रत तो अपने मन की कमज़ोरी को ज़ाहिर करते हैं। और फिर बदला मैं लूँ किससे? उससे, जिसके सजदे मैं दिल की तन्हाइयों में करती हूँ? यह कैसे हो सकता है?''

Soon after this incident, Pammi begins to sense that Chandar’s emotions are once again drifting toward Sudha. Trusting her intuition, she decides to leave him. Following her departure, Chandar experiences a disturbing dream where he sees himself forcefully demanding intimacy from Sudha — equating physical closeness with proof of love. This moment marks the final moral decay of Chandar’s character, and it is here that he truly transforms from a "devta" into the Gunahon Ka Devta.

The reflection calls out his delusions of purity and spiritual detachment, revealing that his so-called “sacrifice” was often a result of fear, pride, or escapism. His pursuit of idealism, instead of elevating him, led him to hurt those who loved him deeply. Though Chander tries to defend himself, his inner voice systematically exposes how his narcissism, indecisiveness, and emotional immaturity left behind a trail of broken trust and missed opportunities.

In the end, the monologue is not just a dialogue with the self—it is a psychological unraveling, a moment when the mask of virtue falls away and Chander is confronted with his real, flawed, and vulnerable self.

We can observe this monologue point by point, each revealing a different perspective on his character:

Critical Analysis of Chander's Monologue:

This passage is a deep psychological and philosophical introspection of Chander’s character. The mirror scene where he argues with his own reflection is one of the most powerful moments in the novel. It is rich with symbolism, existential conflict, and brutal self-exposure.

1. Conflict Between Appearance and Reality:

As Chander looks at his reflection, he sees a version of himself that feels alien — “the reflection was mysteriously smiling.” This moment marks the beginning of his internal breakdown. The confrontation is not with a literal reflection, but with his own conscience — the part of him that refuses to accept the lies he has built about himself.

“Papi! Patit!” (Sinner! Fallen!)The room echoes these words, showing how the truth reverberates within him despite his denial.

2. Narcissism and False Righteousness:

Chander has long viewed himself as morally upright — someone above the ordinary urges of desire and attachment. But the reflection shatters this illusion. He’s told, essentially, “You are not a saint. You are not selfless. You’re a hypocrite who hurt people under the guise of purity.”

He says: “I never forced anyone. Whoever came into my life, came on their own.”The reflection counters: “And yet you used them, rejected them, and called it self-control.”

This is a clear indication of narcissistic delusion — a man who uses his “virtue” as a mask for emotional manipulation.

3. Denial and Habitual Negation (Nishedh):

A key theme is how Chander has always negated things:

-

He negates society (social rules).

-

He negates duty (karma).

-

He negates emotions (Sudha's love).

-

He even negates success and failure.

He is told:

“Your life has been a series of psychological reactions rooted in denial.”

Rather than accept the challenges of life and grow through them, Chander escapes. His so-called “detachment” is really avoidance, not maturity.

4. Inner Turmoil and Self-Deception:

The reflection mocks Chander’s attempt to call himself "pure" and "misunderstood". It accuses him of pride, selfishness, and emotional cowardice. He hurt Sudha, used Binny, and couldn’t even offer stability to Pammi — yet still sees himself as a misunderstood idealist.

“You think you sacrificed? You escaped. You think you renounced? You rejected responsibility.”

It’s a classic case of self-deception — where Chander builds a spiritual image of himself to justify his inability to face love, attachment, and commitment.

5. Lack of Depth and Stability:

The metaphor of a strong but restless wave is telling:

“You were not the deep ocean. You were a powerful but unstable wave, crashing against every shore.”

Chander is intense, passionate, even visionary — but not grounded. He lacks the patience and emotional stability to carry relationships or philosophies to fruition.

6. Symbolism and Allegory:

-

Mirror: Symbol of self-awareness. The mirror reflects the truth Chander hides from.

-

Reflection speaking: His own inner conscience, now louder than his reasoning.

-

“Your soul became a stagnant pond”: His once vast potential has decayed into self-centeredness and stagnation.

7. Philosophical Depth:

The passage critiques the kind of "false idealism" where people think renouncing things is equivalent to virtue. It says real spiritual growth comes not from running away, but from embracing life, relationships, and conflict with a full heart.

And in the second-last meeting between Chander and Sudha, when she returns home, we see that Sudha has become very weak. Chander begins to confess the moral lapses he committed while Sudha was away from him. What is striking, however, is that Sudha never asked for any confession. It seems she is not even bothered by the deeds themselves—what has truly hurt her is Chander’s ignorance, his moral decay, and the emotional distance he created.

Sudha keeps listening silently as Chander admits:

"बस, उसके बाद से तुम्हारे लिए मेरे मन में एक अजीब-सी अरुचि (उपेक्षा) होने लगी। मैं तुमसे कुछ छुपाऊँगा नहीं।"

तुम्हारे जाने के बाद बर्टीआया। उसने मुझसे कहा कि औरत केवल नई संवेदना, नया स्वाद चाहती है—और कुछ नहीं। अविवाहित लड़कियाँ विवाह, और विवाहित लड़कियाँ नए प्रेम... बस, यही उनका चरम लक्ष्य होता है। लड़कियाँ शरीर की प्यास के अलावा और कुछ नहीं चाहतीं... जैसे अराजकता के दिनों में किसी देश में कोई भी चालाक नेता शक्ति छीन लेता है, वैसे ही मानो उस मानसिक शून्यता के क्षण में बटु मेरा दार्शनिक गुरु बन गया।

उसके बाद पम्मी आयी। उसने मुझसे कहा कि क्या आवश्यक है कि पुरुष और नारी के संबंध में सेक्स हो? और फिर उसने ही जवाब दिया—'हाँ, और यदि नहीं है तो प्लेटोनिक (आदर्शवादी) प्यार की प्रतिक्रिया सेक्स की ही प्यास में होती है।'

अब मैं तुम्हें अपने मन का चोर बतला दूँ—मैंने यह मान लिया था कि तुम भी अपने वैवाहिक जीवन में रम गई हो। शरीर की प्यास ने तुम्हें अपने में डुबो दिया है, और मेरे सामने जो अरुचि तुम प्रकट करती हो वह केवल एक दिखावा है।

इसीलिए, मन ही मन मुझे तुमसे चिढ़-सी होने लगी। पता नहीं क्यों, यह संस्कार मुझमें दृढ़ हो गया और उसी के कारण मैं तुमसे नहीं, बल्कि पम्मी को छोड़कर बाकी सभी लड़कियों से नफरत-सी करने लगा।

बिनती को भी मैंने बहुत दुःख दिया। विवाह में जाते समय वह बहुत दुखी होकर गयी।

रही बात पम्मी की—तो उस पर मैं इसीलिए खुश था कि उसने एक बहुत यथार्थ बात कही थी। लेकिन जब उसने मुझसे कहा कि आदर्शवादी प्यार की प्रतिक्रिया शारीरिक प्यास में होती है, तो उसे अपराधी मानकर मैं उससे नाराज़ हो गया। लेकिन अंदर-ही-अंदर, वही संस्कार मेरा व्यक्तित्व बदलने लगा।

After Sudha left, Chandar began to feel a strange disinterest and emotional disconnect toward her. He confesses this honestly. Following her departure, his friend Bat came and influenced him with a cynical view of women—that unmarried women only seek marriage, and married women seek new lovers; ultimately, women are only driven by physical desire. Chandar, vulnerable and emotionally disoriented, began to internalize this belief.

Later, Pammi came into his life and argued that even ideal, "platonic" love eventually seeks physical fulfillment. Chandar began to believe that Sudha, too, had become absorbed in her marital life and physical desires, and that the indifference she showed toward him was just a facade. This belief created a subconscious resentment in him—not just toward Sudha, but toward other women (except Pammi).

He admits that he wronged Bintee emotionally and acknowledges her pain during her wedding. While he initially admired Pammi for her frankness, her statement about physical desire being a reaction to spiritual love hurt him. Still, inwardly, that very idea began to reshape his worldview.

Chandar then reflects—perhaps Sudha’s body never awakened to that desire, but in his case, the guilt and emotional storms rose violently. He ends with a vulnerable confession: that in moments of weakness, Pammi’s genuine physical surrender helped cleanse some of the bitterness within him.

sudha says--

"भागवत में एक जगह एक टीका में मैंने पढ़ा था, चन्दर—कि जिसे भगवान बहुत प्यार करते हैं, उसमें उनका अंश अभिव्यक्त होता है। बहुत बड़ा वैज्ञानिक सत्य है यह! मैं बिनती को बहुत प्यार करती हूँ, चन्दर!"

Sudha reflects on a verse from the Bhagavata Purana that says when God loves someone deeply, He manifests a part of Himself in that person. Through this metaphor, she expresses the depth and purity of her love for her friend Binti, equating it with divine affection.

Chander, in turn, ironically twists the idea and says:

“Now I understand where my sins came from—since you loved me so much, the sins from your personality flowed into mine.”

This moment is tinged with sarcasm, self-blame, and irony. Chander, already tormented by guilt and inner conflict, seems to both blame Sudha’s love and acknowledge his own weakness. if the sins of chandar were the reason of sudha's sins than sudha also loved a true 'platonic love', one sided love but these factor never affected chandar but the physical love for what sudha didnt have any other option left, which litrally made her life hell, became the reason for chandar to have sex with pammi! it was the chandar only who consulted sudha for let the things happen between kailash and her very casually! and after that he blames sudha for his own moral decay!

when for the last time when dr. shukla calles chandar to delhi, he goes there with full exitement, thinking about sudha in all the way but when he reaches there, the reaility was totally different there, sudha had a miss carriage and she was on a death bed, screaming, bleeding. As Sudha lies gravely ill, her physical condition worsens, and her mind fluctuates between clarity and delirium. In her feverish state, she begins to call out for her father and Chander, confusing people around her with figures from her memories—mixing the present with the past. She screams, pleads, and hallucinates, showing both emotional agony and deep longing.

Chander arrives and tries to comfort her, but she initially fails to recognize him, accusing him of cruelty and betrayal for not being by her side earlier. Amid moments of lucidity, Sudha expresses affection and care—asking for forgiveness, worrying about her loved ones, and giving emotional responsibilities to Chander and Bintee. She tells Bintee to take care of their father and urges Chander to marry and live a fulfilling life.

As her condition deteriorates, doctors rush in and declare that her situation is critical. Despite some brief signs of recovery, including tender moments with Chander and her father, her strength fades.

Sudha’s final moments are a blend of hallucinations and emotional outpouring. She imagines leaving for another world but reassures Chander that she will return. In her last act of love, she clings to Chander’s hand, speaks of her undying affection, and finally collapses in his arms—her head falling onto his shoulder. As she dies, her words echo with both resignation and eternal love.

The clock strikes two. Sudha is gone. her death is slow, poetic, filled with grace and lament. She becomes a symbol of ideal love crushed by societal and personal failure. Sherbet, nankhatai, books, exams—mundane elements placed in surreal contexts represent her fractured perception and desire to relive the ordinary before departing forever. Her death is her most powerful act: a silent scream that echoes in the soul of the reader.

in the end, chandar fills forhead of binati with the ashes of sudha and thats how he fulfils the last wish of sudha of marrying Binati. again here i feel the loop hole in chandar's character. he could simply have stayed unmarried for life time and keep loving sudha 'platonically' but he choses to marry! As seen in the past, Chandar often finds a new girl to forget Sudha—and this time too, in an attempt to move on, he ends up marrying Binati. and even while fillimg forehead of BInati he dosnt even care to ask her whether she wants to get married to him or not!

many readers finds the 'love story' of chandar and sudha attractive, for some the novel become most remebring through the platonic love element but for me this book will always remain alive for sudha who wanted to study,who wanted to become independent, who loved chandar without any expactations, who cared for her father and died as a pray of society, patriarchy, hypocricy, narcism of chandar and dr. shukla.

While summing up...

This novel remains profoundly relevant even today, not because society has progressed, but because in many ways, it hasn’t. The emotional patterns it explores—using one person to forget another—still dominate modern relationships, often cloaked under the guise of healing or moving on. Love marriages, though more visible now, continue to face resistance within conservative families. But perhaps the most unsettling continuity is the unchallenged narcissism of male characters—then romanticized, now normalized. What Bharti presented through Chandar as emotional turmoil is, in reality, a reflection of male entitlement and emotional irresponsibility—an issue that still persists in the name of love. Controlling women emotionally, mentally and physically by men and society will always remain relevant and timeless.

Gunahon Ka Devta is not just a love story; it’s an emotional battlefield where ideals, relationships, desires, and societal expectations collide. Through the silent yet soul-stirring bond between Chandar and Sudha, Dharamveer Bharati compels us to look within ourselves—to question what love truly means, how far we bend for it, and what we lose when we suppress our emotions in the name of morality or duty.

While Bharati may have tried to portray Chandar as a philosophical and morally complex figure, I believe his flaws—his escapism, indecisiveness, and emotional contradictions—make him deeply human, but also deeply weak. In contrast, Sudha’s unwavering, selfless love and quiet endurance leave a lasting imprint on the reader’s heart.

Even today, decades after its publication, Gunahon Ka Devta remains relevant because the dilemmas of love, societal pressure, and emotional vulnerability are timeless. The novel reminds us that sometimes, the most painful stories are not of war or separation, but of love that is never spoken, never fully lived, and yet never forgotten.

It is widely believed in literary circles that 'Ret Ki Machhli', written by Kanta Bharati, was her response to Dharamveer Bharati’s iconic novel Gunahon Ka Devta.

In the world of Hindi literature, it has often been said that Sudha—the central character of Gunahon Ka Devta—was inspired by Kanta Kohli, the woman Dharamveer Bharati once deeply loved. Kanta was not only Bharati's first wife but also the daughter of his mentor, Professor Dhirendra Verma. As Bharati immersed himself in literature under his guru’s guidance, he also fell in love with Kanta, and began to see the essence of Sudha in her.

However, unlike the unfulfilled love of Sudha and Chandar in the novel, Bharati did not accept separation in real life. He married Kanta, but disillusionment followed soon after—within just a month, he began to drift away. During Kanta’s pregnancy, it was Bharati’s own student, Pushpa Sharma, who took care of her. It is said that Bharati fell in love with Pushpa as well, and soon found himself emotionally torn, having already made promises of love to her.

Eventually, the marriage between Kanta and Dharamveer Bharati ended, and he went on to marry Pushpa Sharma. Pushpa herself was a writer, and the couple had three children: Parmita, Kishanku, and Pragya.

Against this backdrop, Ret Ki Machhli stands not just as a literary work, but as a personal statement—possibly a reply from Kanta Bharati, who chose to write her side of the story not through accusations, but through literature. So, let’s see what Kanta Bharti has to say in Ret Ki Machhli — in the next blog...